“I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest.”

T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land. ll. 228-229

William Blake’s relationship with Dante’s Divine Comedy is an overt one; his illustrations ascertain his knowledge with the narrative poem. Ample scholarship has examined the choices Blake made in constructing his accompanying artworks[1], an investigation continuing to be explored.[2] Similarly, critical works of Blake in terms of androgyny and gender ambiguity is extensive[3], making transparency and transgenderism familiar issues in Blake. What is evident in the Blake canon is the relevance of these trans ideas; that is, the fluidity and mobility of the many disciplines he surveys. Blake’s vision is not static, but one increasingly mutable, inherently trans. It is from this understanding I introduce the mythological, transgender auger, Tiresias, into conversation with Blake. Tiresias unites concepts inherently Blakean, a trans-character himself, and one that Blake would have been aware of due to his minor but nonetheless significant appearance in Blake’s illustrations to Dante. Relying on Dante’s and Blake’s presentation of Tiresias, along with the discourse that Tiresias’ character queries, I will bring Tiresias into conversation specifically with Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and more generally across the Blake canon. Whilst condemned by Dante, but subconsciously celebrated in Blake, I argue that despite Tiresias not being openly explicit or referred to in Blake, the issues he is associated with are ever present in Blake’s thought, and thus, Tiresias is transparent in Blake. This idea of Tiresias as not being merely absent, but simply invisible, inherently existing in Blake but just transparent in that we do not immediately detect him, I will refer to as the Tiresias ‘politic’.

The prefix ‘trans’ opens our enquiry and points to many relevant issues in this ‘politic’. The Latin trāns or trare, refers to the act of passing through or crossing over, indicating a mobility and mutability, thus effective in both the terms transgender and transparent, two conflicts incessantly related to each other throughout Blake. Tiresias’ transparency does not measure or determine his existence within Blake texts, similarly his physical absence not indicating a lack of presence. Tiresias gains a transparency in that his vision disappears, a transparency that indicates a sort of lack, but he also exercises a transparency of vision in his augury; an ability to see what others cannot, to transparently see what to others, is opaque. Therefore, this idea of something not being there does not indicate a lack of existence; consider genitalia, a woman’s ‘nothing’[4] by definition refers to the lack of a certain ‘thing’, thus stressing the ‘thing’ and making it overt. In this way, the ‘thing’ is inherently present, as it is impossible to describe its absence without reference to the ‘thing’ itself, dissipating the intention of ‘nothing’ and authorising it into some-thing. It is the same with transparency; it is not as straightforward as declaring something non-existent by way of its physical absence. Blake assists with the idea of there being presence in absence, and something in nothing. Blake confronts understandings of invisibility; “Why art thou silent and invisible” (l. 1) he asks God in To Nobodaddy. If invisibility is correlational to inexistence, then Blake would lose faith in a God, and Tiresias would bear no relevance to Blake, invalidating my argument. The invisibility Blake describes however, is not in reference to God’s existence that Blake describes, but the intangibility of religion as an institution, from “every searching eye” (l. 4). This repeats itself in The First Book of Urizen when Blake refers to “The Net of Religion” (l. 469)[5]. It is clear that he deems God and religion as two separate, detached entities. Blake therefore promotes this idea of invisibility differing from inexistence. His idiosyncratic, eidetic vision parallels Tiresias’ own augury. In To The Queen, Blake suggests you see more when eyes are closed (or blind in Tiresias’ case): “mortal eyes cannot behold; But, when the Mortal eyes are clos’d (…) the soul awakes and, wondering, sees” (ll. 2-5). This is an inherently Tiresian notion of the soul seeing as opposed to the eye, the eye searches whilst the soul sees effortlessly; this deems Tiresias’ blindness as redundant, his ability to see has not been impaired. It is both a Blakean and Tiresian idea that there is a disconnection between the eye and sight, both establishing themselves as augurs.

It is important to identify a pre-Dante archetype of Tiresias to inform a conclusive impression of him. First introduced in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Tiresias “was somewhat amazingly changed from a man to a woman for seven years” (Ovid, 108) after striking two mating snakes, until finally repeating this blow to reverse back to his original sex. His experience of each sex led him to reveal to the female God Juno that women derive greater sexual pleasure than men, for which she “condemned his eyes to perpetual blindness” (Ovid, 109). The male Jupiter then compensated him with the gift of augury[6]: here stands our archetypal Tiresias. Intrinsically protean, Tiresias undergoes a series of changes: starting with one of gender, he is transformed from male to female, he then returns to his male state, undergoes a loss of sight, but regains the ability of augury. Even Dante’s depiction of Tiresias submits him to further transformation as he is punished among other seers by having his head reversed. His state as a figure is not solid, but malleable, not opaque, but transparent, impossible to grasp or register. In The First Book of Urizen, Los’ transformation is one most relevant in conversation with Tiresias. The changes that these two figures undergo are not dissimilar, whilst Tiresias develops into another gender, Los divides, mitosis-like, into two. Paul Mann states that “The Urizenic genesis is the production or rather the continual reproduction of selfhood” (Mann, 56), indicating that personal transformation, or ‘genesis’, releases further development of character. Each of these figures develop in that they gain privy to individual male and female experience, Los simultaneously, Tiresias one at a time; “I Tiresias have foresuffered all” (Eliot, l. 243)[7]. Comparing their positions questions why Blake has not merely distorted Los into some other being, but has chosen to almost replicate him instead. In The First Book of Urizen, Blake describes the birth of the child of Los and Enitharmon as “the birth of the human shadow” (l. 365). Enitharmon being Los’ “own divided image” (l. 338) reminds us of their Tiresian quality, a duo to Tiresias’ single figure, but gender fluid still. The fact that their offspring is then a ‘shadow’, suggests a translucent quality akin to Tiresias’ transparency. It seems consistent in these examples that such gender fluidity culminates in an ability to be transparent, to be intangible but present, for a birth does not create something that is not there. Upholding Mann’s opinion, Tiresias’ gender change, and then reversion, is developing: much like how he develops in his representations from Ovid to Dante.

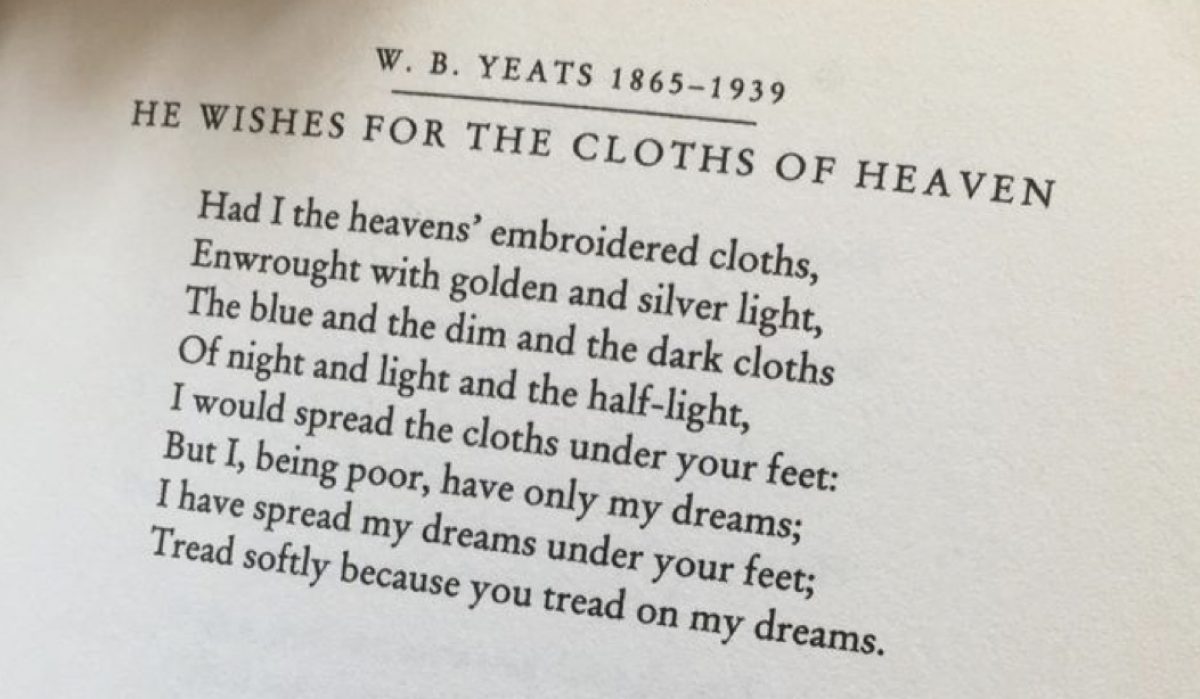

With Ovid establishing a clear basis for the Tiresias figure, we can now examine Blake’s interpretation of an already laden figure in relation to Dante’s use of the seer. Whilst Blake did not live to complete his series of illustrations, we can deduce a great deal even from his minor mention of Tiresias. “Blake was not passively depicting Dante’s works, but was engaged in an intellectual and artistic dialogue with his Italian peer” (Pyle, 1): it is therefore important to not dismiss any creative choice made by Blake, each one an intentional decision. It is impossible to decipher which of the three male figures in Blake’s illustration is Tiresias, the only recognisable character being Tiresias’ daughter, Manto, identifiable due to her female portrayal (Fig. 1). All four share the same reversed deformity, yet Blake dresses the male figures with long beards, Bard-like and distinguishable in Blake’s work as an indicator of false belief[8], challenging Tiresias as the seer to Blake’s bard. It is important to note the hesitancy with which Blake used the watercolours here. This does not refer to colour choice, which could be a pure issue of availability, but the lightness with which the paint is applied, providing the image with a literal transparent quality. The forms are visible, but not opaque: there is a translucence with which the figures seem momentary, there, but simultaneously not. In this way, Blake’s own Tiresias is literally transparent, both physically in his illustration, and indirectly in his work. Whilst the illustration confirms that Blake would have had an indirect awareness of Tiresias at minimum, there lies a criticism of sorts masked in the bearded heads. If Blake’s struggle is with the ‘false belief’ adorned by the soothsayers, that is a purely religious matter and not one that interferes with our enquiry of augury, gender, or bodily mutation that echoes Tiresias in Blake; “the strict definition of sin punished – simony or divination – is less important to Blake than the more general corruption of true religion” (Pyle, 204). In this case, we can detach from Blake’s religious opinions on religious authority, and continue to acknowledge these occurrences in which Tiresias is transparent throughout Blake, all the while acknowledging how this note attempts to confuse the ‘politic’.

Whilst Blake’s accompanying images reveal something of Dante’s poem, Dante specifically is condemning Tiresias amongst other soothsayers for their divination, and does so by physically mutating them; “twisted around between the chin and thorax. The face of each looked down towards its coccyx. And each, deprived of vision to the front, Came, as it must, reversed along its way” (ll. 10-15). It is important that Dante imagines Tiresias undergoing a physical punishment for psychological trespass; “Dante meditates on the ways in which the human mind, by its prophetic pretensions to know the unknowable, can distort our natural relationship to a particular time and place. Our bodies define us in our connections with the world around us, and suffer when the mind seeks to transcend those limits” (Kirkpatrick, 390). This idea of the physical body as defining to the external world is one Blake resists. To deem bodily experience as tangible and still, as determinative, is to resist and degrade transformation and mutation. It is an idea that resists the Tiresias ‘politic’ altogether, as to be transparent is by nature to be intangible, complicated to define. This implements a clear connection between bodily mutation and the mental transcending of bodily limits, in Tiresias’ case, augury. Tiresias’ vision is distorted by his reversed position in Dante’s poem, as illustrated by Blake, due to his transcendent vision. There is also a sense here of an inevitability to escape change or transformation in that the punishment for Tiresias’ changes in life are bodily reversal in death. That is to say that even when a change is being condemned, the punishment for it is further change; whilst in life he looked transcendentally forward, in death he is destined to literally look behind. If we are to pair the protean, transparent, ever changing Tiresias with Dante’s Hellish figure, we are presented with a productive character within a historically degenerative environment, authorising Tiresias’ mutability and transparency as immortal and inescapable.

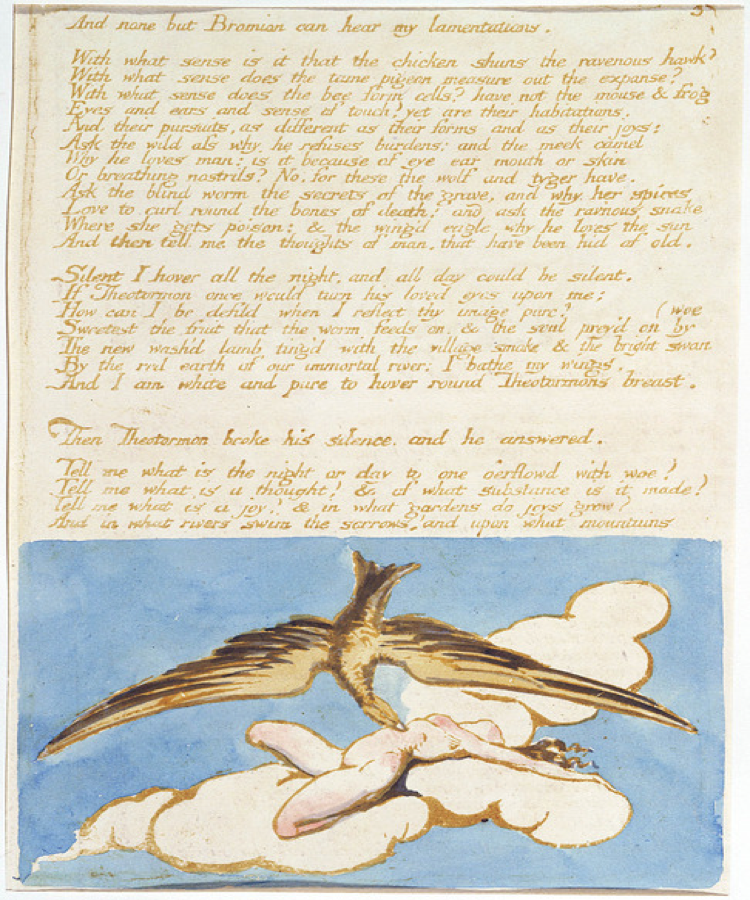

Dante unites the male and female domains in his description of Tiresias when he states “he needs must strike a second time, and shake Again at coupling snakes his witch’s wand” (ll. 40-45). To combine the ‘witch’ and the ‘wand’ is emblematic of both Tiresias male and female experiences: the ‘witch’, akin with Blake’s “secrecy that gains females’ loud applause” (ll. 9-10)[9], that marks the phallic ‘wand’. Both Dante and Blake have acknowledged this tendency to distrust the female sex, to mark them with secrecy and witchcraft. Yet more complicatedly, Blake inverts Dante’s explicit gendered allusions in his Visions of the Daughters of Albion. Here, Blake’s “worm” is a “her” (l. 71), his “snake” a “she” (l. 73) and yet his “meek camel” a “he” (l. 68). Blake inverts classic phallic images and brands them female, and gives stereotypically male images reproductive and weak qualities. Blake does not see gender as binaries, but as a spectrum upon which beings can transport, much as Tiresias does. Blake has an “awareness that sexual equality cannot be achieved by simply acknowledging the difference between masculine and feminine traits and allocating to each a positive mutual identity, because in many binary oppositions – aggression/passivity, intellect/emotion, spirit/flesh, culture/nature – men have secured the first quality, thus leaving women to be aligned with the second quality. In the world of Blake’s imagination there is no such thing as an essential biologic manliness or womanliness” (Hayes, 146-147). Dante’s juxtaposition of the ‘witch’s wand’ thus fails, as he has to submit to the binaries that make Tiresias such a problematic figure to him, these binaries juxtaposed therefore sort of cancelling each other out, adding to Dante’s complication with Tiresias. Hayes and indeed Blake however demolish these binaries, allowing Blake’s masculine ‘sun’ and feminine ‘worm’ to exist, where Dante’s ‘witch’s wand’ does not. In this way, despite Tiresias’ textual presence in Dante, he fails to be grasped concisely, whilst there is a far greater understanding of Tiresias’ fluidity in Blake’s re-organization of gendered words, not an absence but a transparence: the complication that is the Tiresias politic. Blake further complicates this transportation from the domains of male and female, to how one gender alone might travel across its stigmas, as Oothoon asks “Art thou a flower! Art thou a nymph! I see thee now a flower: Now a nymph!” (ll. 6-7). Blake abolishes sexual expectation[10] in order to create a situation where one might be both ‘nymph’ and ‘flower’, to fluctuate between two established categories. This categorisation Tiresias resists; the politic described is explained by episodes such as this in which neither Blake nor Tiresias obey binaries, but deem them a mere spectrum. There is no space in Eighteenth-Century society for Blake’s world in which the nymph might be a chaste flower, just as there is no space in Dante’s Inferno for an auger who disobeys the laws of time.

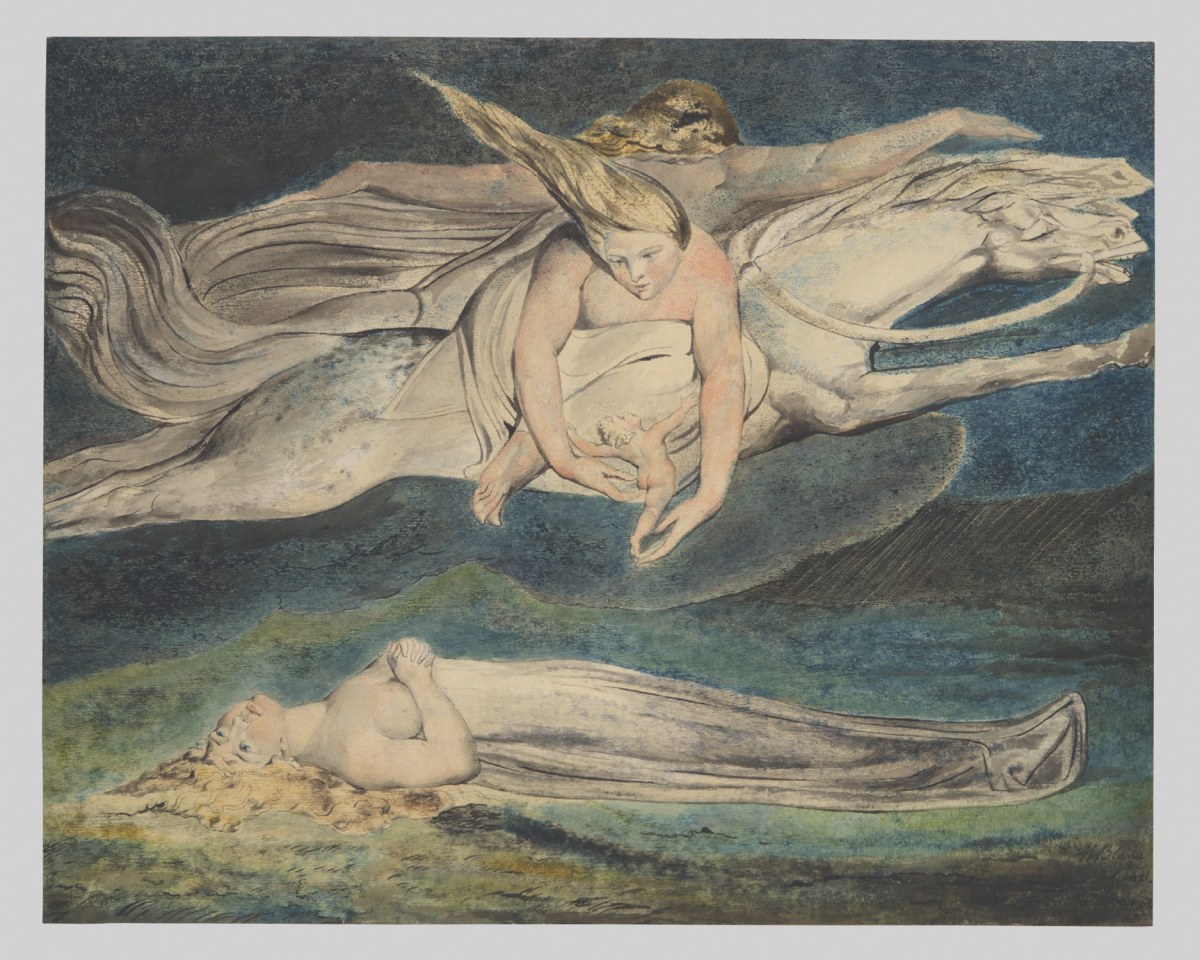

Having focused on this reversal of gender associations, we can determine that they are Tiresianically inconclusive, transparent – veiled from clarity. In The Argument of Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Oothoon claims “I was not ashamed; I trembled in my virgin fears And I hid in Leutha’s vale!” (ll. 2-4). To hide in a vale serves as an antithesis to ‘shame’ here. Whilst it is possible to hide in a vale or valley, it is similarly possible to be veiled. The connection between shame and veiling is a problematic one, involving questions of modesty, and a knowledge of what to be ashamed of, and what to veil. Therefore, to not bear shame like Oothoon, implies a sexual confidence and resistance to expected modesty. However, this does not dictate Oothoon’s sexual stance indefinitely. Following her rape, she urges “Theotormon’s Eagles to prey upon her flesh” (l. 36). There is unease here as Oothoon reduces herself to matters of consumption in light of her loss of chastity, and yet more unease in Blake’s depiction of her desire to be ‘preyed’ upon. His illustration of this scene upholds this unease as what is essentially a violent, degrading act, is depicted as almost holy, the vulnerable Oothoon laid on her back, upon a heavenly white cloud, the celestial image somewhat ignoring the violence it illustrates (Fig. 2), and female capability to be raped. This desire for such a violent act immediately after undergoing the first, is uncomfortable on Blake’s part as he delves into a problematic rape justification. This desire of a penetration of sorts and its confidence in doing so complicates Oothoon’s stance on shame, and contrasts to Tiresias’ lack of sexual confidence on encountering the mating serpents. Blake describes Oothoon as bearing a guilt in this self-disciplining episode, but the confident desire indicates she has nothing to be ashamed of, nothing to veil.

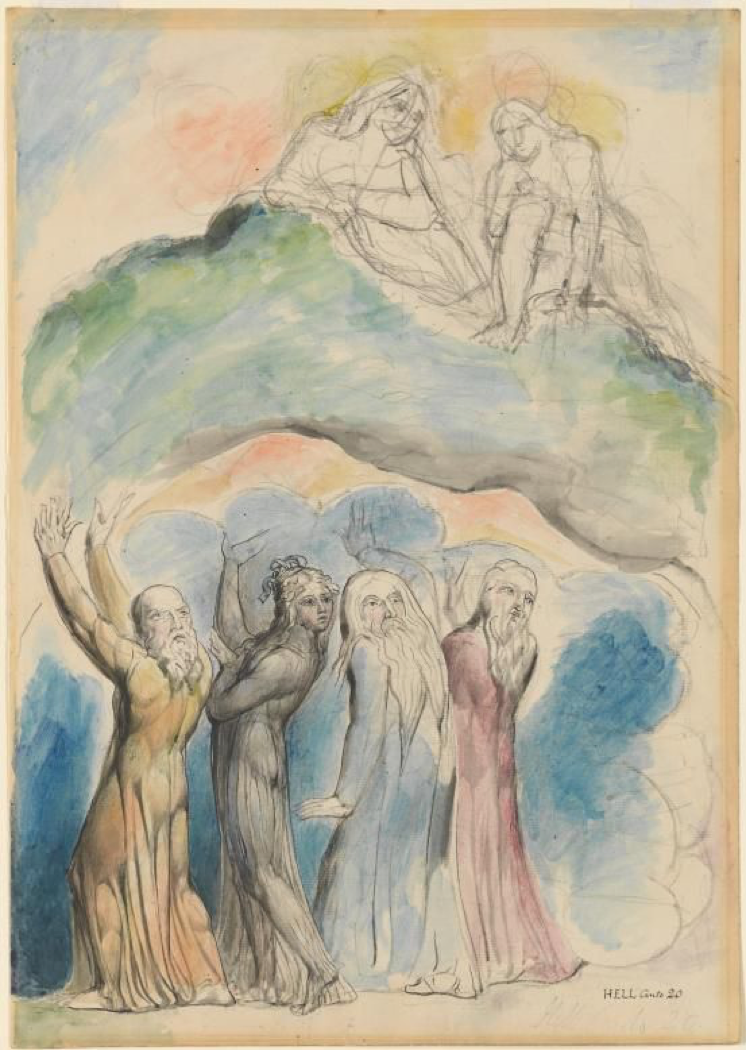

Subsequent to her self-torture, Oothoon pleads to “rend away this defiled bosom that I may reflect the image of Theotormon on my pure transparent breast” (ll. 38-39). At this point, Blake disassociates shame with sexual experience by at once acknowledging a ‘defiled’ breast, and yet simultaneously deeming it ‘pure’. To be transparent thus reinforcing a visibility of its own accord as we have discovered, Oothoon is no longer veiled, she is not shameful. There is a consensual exposure taking place here, Oothoon is willing to expose her ‘transparent breast’, thus emphasising exposure through transparency and Tiresias’ existence in a lack thereof. If to be transparent is to be completely vulnerable, accessible, then it is to be penetrated. This is a tangible invisibility as opposed to the intangible invisibility of Blake’s organised religion. To self-declare herself in this state Oothoon announces total ownership, via her accessibility to others. It is in employing Blake in this way that we can observe how penetrating Tiresian tropes inform our comprehension of such ideas in Blake. The three characters illustrated in Blake’s frontispiece to the Visions seem in equal turmoil (Fig. 3). Their hanging, anxious head portray their shared pain, and their almost unidentifiable, naked, intertwined bodies relate them all to each other. Whilst Oothoon is attached behind supposedly Bromion, it is not her that seems in such angst at her captivity as it is him: it is his body that is most compromised, most distorted, the chains shackling his feet. Their manacling together connects their physical bodies and makes the individual indistinguishable. In this way, Oothoon and Bromion are one, male and female counterparts of a single unity. They are inherently Tiresian, as through the character of Bromion, Oothoon’s masculine self and restricted desire is explored. Blake explores not only the possibility of Tiresian gendered experience, but the potential of such knowledge and expression.

Tiresias is an inherently Blakean figure on account of his fluidity and contradictions: he is blind and yet sees, male and female, absent but present. Whilst a Tiresian approach might not be conclusive to understanding Blake, there is a relevance in studying the two alongside each other, Tiresias lending himself as one possibly interpretable metaphor for some of Blake’s vast allusions. Tiresias develops from Dante’s condemned seer, to Tiresian ideas being subconsciously celebrated in Blake. He embodies a literary development from a damned figure, to one that attempts to explain modern ideas in Blake, the literal auger. He is a mythological character in conversation with Blake’s own mythopoeia, in so far as his characteristics are not concrete, much like the evolving Los or gender defying Oothoon. Unbeknownst, Blake is a Tiresian advocate; he just does not declare it consciously, but indirectly his texts address Tiresias himself: “ask the blind worm the secrets of the grave” (l. 71)[11]. For the purposes of this argument, we could read this as an instruction, to consult Tiresias in order to start to unravel the ‘secrets’ of Blake’s work. Indeed, whilst this blind seer might only parallel a select few incidents in Blake, his presence is certain; Tiresian thought is woven into Blake’s most dominant ideologies, thus making this ‘politic’ very much worthwhile.

Word Count

3174

Bibliography

Blake, William. Selected Poems. London: Penguin Classics, 2005. Print.

Blake, William. The Necromancers and Augers, 1823-27. Copy 1, Object 37. Pen, Ink and Watercolours over Pencil. 52.5 x 37.0cm. National Gallery of Victoria.

Blake, William. Visions of the Daughters of Albion, 1793. Copy A, Plate 5. Print. 17.2 x 12.9cm. The British Museum.

Blake, William. Frontispiece to Visions of the Daughters of Albion, 1793. Copy P, Plate 1. Print. 17.1 x 11.9cm. Fitzwilliam Museum.

Bruder, Helen P. Blake, Gender and Culture. New York: Routledge, 2016. Print.

Dante Alighieri. “Canto 20”. Inferno. London: Penguin Classics, 2006. 168-175. Print.

Eagleton, Terry. “Nothing”. William Shakespeare. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986. 64-70. Print.

Eliot, T.S. Selected Poems. London: Faber & Faber, 2002. Print.

Eliot, T.S. The Sacred Wood and Major Early Essays. New York: Dover, 1998. Print.

Hayes, Tom. “William Blake’s Androgynous Ego-Ideal”. ELH. 17.1 (2004): 141-165. JSTOR. Web. 15th Dec. 2017.

Kirkpatrick, Robin. “Commentary and Notes”. Inferno. London: Penguin Classics, 2006. 315-450. Print.

Mann, Paul. “The Book of Urizen and the Horizon of the Book”. Unnamed Forms: Blake and Textuality. Ed. Nelston Holton and Thomas Vogler. Berkley: University of California Press, 1984. Print.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. London: Penguin, 2004. Print.

Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. Print.

Pyle, Eric. William Blake’s Illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Study of the Engravings, Pencil Sketches and Watercolours. U.S.A.: McFarland & Co, 1959. Print.

Terzoli, Maria Antonietta. William Blake: The Drawings for Dante’s Divine Comedy. Germany: Taschen, 2018. Print.

Notes

[1] The most celebrated arguably being Eric Pyle’s William Blake’s Illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy: a study of the engravings, pencil sketching’s and watercolour, to which I have used to aid my own enquiry. Full citations in Bibliography.

[2] A revision of Maria Antonietta Terzoli’s William Blake: The Drawings for Dante’s Divine Comedy, is to be published later this year, consisting of close readings alongside the initial illustrations: this highlights the depth of analysis there is to be made in the illustrations, the implications of which continuing to unfold.

[3] Bruder argues in Blake, Gender and Culture that hermaphroditism in Blake refers more to the Renaissance ideas of ideal or monstrous forms as opposed to any gender-specific meaning.

[4] Terry Eagleton explains that “there is some evidence that the word ‘nothing’ in Elizabethan English could mean the female genitals (…) a woman appears to have nothing between her legs, which is alarming for men as it is reassuring” pp. 64 ‘Nothing’ from William Shakespeare, full citation in Bibliography.

[5] Tiresias’ story instigates a religious conflict, he is inverting a biblical message; consider the fact that Tiresias is punished for striking a pair of mating serpents. Associated with temptation, Tiresias’ punishment indicates that he has disturbed something more sacred; something that interrupts the classical creation story. Blake endorses this notion in To Nobodaddy, he observes why “none dare eat the fruit but from the wily serpent’s jaws” (l. 8). This seems problematic as when Eve dared to be tempted by serpents, she was punished. The thought that we ought to dare as Eve and Tiresias have again promotes that there is some holy revelation to be discovered by the creatures.

[6] The story of Tiresias in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, pp. 108-109 as cited in Bibliography.

[7] Eliot employs Tiresias in his chapter The Fire Sermon of The Waste Land, in the notes of which he explains; “Tiresias, although a mere spectator and not indeed a ‘character’, is yet the most important parsonage in the poem, uniting all the rest… What Tiresias sees, in fact, is the substance of the poem” (Eliot, 60). Whilst not active in Blake, there is a sense of his spectatorship that Eliot describes, his constant conversation and interaction with Blake. This complicates the idea to this point of Tiresias’ being present in his ‘absence’ to the more active position of spectating. This does not change his transparent stance, but rather promotes him from merely being alluded to, existing (passively) to actually spectating and ‘seeing’ Blake’s world (actively).

[8] Pyle explains in his Illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy: a study of the engravings, pencil sketching’s and watercolour that Blake did not live to complete his illustrations (1), and describes the Blakean use of the beard as symbolic for false belief, relating to Blake’s angst with religious truth (203).

[9] From To Nobodaddy.

[10] It was an Eighteenth-Century understanding the women could be categorised into one of two realms; that of the chaste woman or fallen harlot; Mary Poovey’s The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer depicts Eighteenth-Century examples of female expectation.

[11] From Visions of the Daughters of Albion.